Latest Critic Reviews

Latest User Reviews

Critic Reviews

Details

Summary

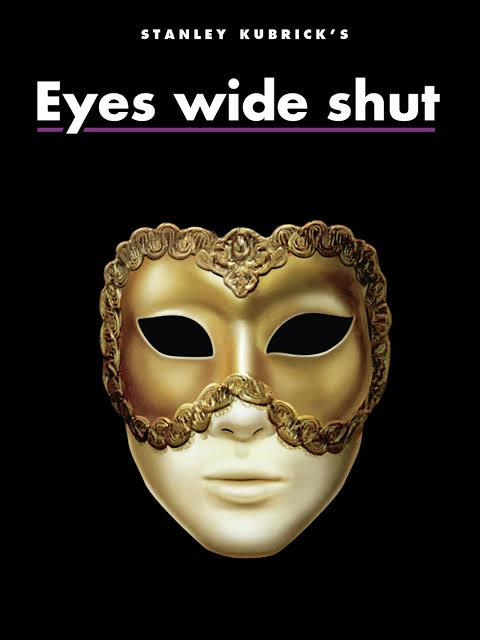

Sexual Obsession, jealousy and dreams are surrealistically examined in “Eyes Wide Shut”, the haunting final motion picture from Stanley Kubrick. While not quite in the same league as some of his earlier works like “Paths Of Glory”, “2001: A Space Odyssey” or “A Clockwork Orange”, “Eyes Wide Shut” is a film that does stay with you for quite some time.

Dr. William Harford (Tom Cruise) and his beautiful wife Alice (Nicole Kidman) seem to live in a dream world: they have a magnificent apartment, a beautiful daughter and a happy marriage. When we meet the Harfords, they are heading to a Christmas party held by the ultra-rich Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack). Each one is hit upon: Bill by two very attractive models and Alice by a handsome older man. The temptation is there for both of them, but the Harford’s are faithful to each other and refuse the advances.

Still, those harmless events prove to be troublesome for the couple. The following night, while sitting around smoking grass in their bedroom, Alice strikes a conversation about the two girls at the party that were falling all over Bill. He brushes it off, which only infuriates her more. Angry for Bill’s lack of honesty and insight when it comes to sexual impulses, she decides to tell him about her own: a detailed confession of how a naval officer had a sexually consuming effect on her when they had gone on summer vacation a few months prior. She never acted on the attraction, but it was a desire that was so powerful that she would have been willing to give up everything to be with the stranger.

The soliloquy has a powerful effect on Bill, who heads out into the cold, dark winter’s night immediately after his wife’s tale to respond to a call that one of his patient’s has died. This, however, is only the beginning for the doctor as he begins a journey that can only be called surrealistic. First, the daughter of the deceased (Marie Richardson) confesses her love to him. Later on, he winds up heading back to the apartment of a prostitute named Domino (Vinessa Shaw) with every intention of betraying Alice. Fate intervenes and the event doesn’t take place, but that is hardly the end of the night’s festivities. He runs into an old medical school buddy named Nick Nightingale (Todd Field) who happens to be playing at a most unique costume party that has Bill both intrigued and excited. Nick tells him to forget about it, Bill has other plans.

Upon acquiring a cloak and mask, Bill manages to get into the party (you need to know the password to get in) which turns out to be a ritualistic orgy of masked decadence. When Bill is caught by the people running the event, he is “rescued” by a half-naked masked woman that had urged Bill to escape while he could. He leaves but soon finds that his impulses and curiosity may not only have cost him his precious private world, but it may have also cost him the lives of one or two other people.

The last third of the film, the aftermath following the orgy, doesn’t have the power and mystique of what led up to it. It settles into the murder mystery scenario that comes with an all-too pat and convenient summary from Ziegler. Yet, it is still compelling to watch Bill and how the events of the night before have had a somewhat devastating impact on him. He is changed and redeemed. While his eyes have been opened, his fidelity to Alice has been reinforced and is stronger than ever.

A running theme with a Kubrick film has always been the dehumanizing of the film’s lead male character (Full Metal Jacket, The Shining, 2001 and A Clockwork Orange are the strongest examples). Here, the theme is more of re-humanization, one that ends the film not with a uneasy feeling of doom, but one of hope, a feeling the viewer has not been able to bring out of a Stanley Kubrick since 1968’s “2001: A Space Odyssey”.

The film also stands as perhaps the most personal of the latter half of Kubrick’s career. While “Full Metal Jacket”, “The Shining”, “2001” and “A Clockwork Orange” were all great films, they were distant emotionally. They were well acted and scripted, but getting inside the characters was a problem with these films. We were more consumed in the sets and how he set up and executed a scene. But with this story, which he co-wrote with Frederic Raphael (based on the Arthur Schnitzler little-read “Traumnovelle”), Kubrick couldn’t rely on funky setups and amazing sets. It is a character piece, not a director’s showcase. His style is evident here and it does strike the necessary chords, but he does let his cast come alive and allows them to give the characters life and hope.

After a couple of misfired attempts at bringing their real-life chemistry to the big screen (Days Of Thunder, Far and Away), Cruise and Kidman both turn in powerful and realistic performances. Cruise nicely underplays his part, never going overboard in the scene-chewing department and always allows the supporting cast to come through and show their best as well. Kidman, despite being missing from most of the film after Alice’s big fantasy confession, really shines in her part (and no, I am not talking about her various stages of undress.). She portrays Alice as a person who seems to be in touch with her desires and emotions and how to deal with them far better than her husband. This little edge gives both Alice and Kidman a more lasting impression on the viewer, an impression that hopefully the Academy will remember come next Spring. Their scenes together work extremely well here, no doubt fueled by their real-life marriage. One just hopes that they were just acting and not bringing excess baggage onto the set from home.

The supporting cast also turn in great, small performances, the standouts being British actor Alan Cumming as a gay hotel desk clerk and Rade Sherbedgia as a costume-store owner who seems to have no problem prostituting his 16-year old daughter. Cumming is downright hilarious, Sherbedgia is downright creepy. Pollack, Richardson, Field and Shaw are all also impressive in their limited screen time.

As with every Stanley Kubrick production, the technical aspect is a much a curiosity to serious filmgoers as the acting and directing is. Larry Smith’s photography shifts from dreamlike (the Christmas party in the beginning, the blue/twilight tone of the apartment in the dark) to frightening (the ritualistic orgy). It also seems to be very grainy, which one would assume is an effect that Kubrick and Smith were going for. As always, the choice of music is fantastic. From Chris Isaak’s “Baby Did A Bad Bad Thing” to Shostakovich’s “Waltz 2 from Jazz Suite” to Jocelyn Pook’s mesmerizing score, this score adds greatly to the proceedings. If there were a false note to Stanley Kubrick’s perfectionism, it would have to be the London sets that were to stand in for New York City. Watch closely to the backgrounds and buildings, you will realize that it’s the same block in different clothing. Not a big deal, but one would have hoped for a bit more.

This leads us to the most controversial technical aspect: the digital masking of certain sexual acts. It is really sad that the dinosaurs at the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) think violent acts are okay to be shown in graphic detail, but not people making love (no wonder this country is so screwed up!). This is an adult film, one that earns it’s “R” rating. It was never meant for kids, it was never marketed at kids. So why then does the MPAA feel that its adult audience needs to be treated like kids? Chances are that the people watching the film have committed the same acts the actors on screen are stimulating, so it’s nothing new to us. This censorship comes off as the equivalent of urinating on Kubrick’s grave.

Whether you liked or hated his work, one could not deny that Stanley Kubrick’s work was unique, a vision that had not been seen before, nor will ever be seen again. His work sparked debate, it made you think, then rethink what you thought of what you had just seen. This definitely applies to “Eyes Wide Shut”. Is it a great film? For the most part, it is. Had it been trimmed by about 15-minutes in the last third, it might have had more of a punch. Yet, I feel uncomfortable cementing my thoughts on the film after only one viewing. His films have a way of seeping into your sub-conscience days after viewing them. Fellow colleagues of mine scoffed at my delayed reaction to the film, stating that it is just a film and first impressions are what count. Usually, this is true. But, this is a Stanley Kubrick film, one in which my opinion may change and much more will sprout up from repeated viewing. It is one that will cause many debates, an aspect that I welcome greatly. I think Mr. Kubrick would have wanted it that way as well.

Related Movies

Related News